Participating artists: Dimen Abdulla, Benedikte Bjerre, Alfred Boman, Elis Monteverde Burrau, Militza Monteverde Burrau, coyote, Jenny Kalliokulju, Essi Kausalainen (with ensemble), Ulrika Lublin, Marthe Ramm Fortun, Ursula Reuter Christiansen, Sally von Rosen, Eetu Sihvonen, Edit Sihlberg

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

Poetry has a way of speaking directly to our bodies. Rather than taking the detour through intellect – offering up theoretical frameworks to consider – it reaches straight into our aesthetic sensitivity. Of course, themes may be present. But perhaps more important is the way words are placed like pebbles in our mouths, whether they have the ability to penetrate solar plexus or leave behind a faint taste of metal. Poetry pulls us beyond meaning, into a different reality – ruthlessly so. Otherwise, it’s not doing its job.

In relation to contemporary art at the twilight of late capitalism, one might say that poetry has been allowed to develop more independently, under its own authority. Could it be because poetry resists commodification – because it doesn’t easily bend to market logic? That neoliberal systems, even in these end times, still haven’t fully laid claim to it?Poetry has remained a narrow thing – largely untouched by institutions, higher education, checklists, purposes, or middlemen. Might that be one reason why it is once again stepping forward as something vital and important?

Art, on the other hand, finds itself in a kind of crisis. Or rather, it’s not the art itself, but perhaps the way we’ve chosen to handle it. Over the past hundred years, art has been institutionalized, commercialized, domesticated, theorized, systematized, tamed, and categorized – to the point where we sometimes struggle to understand what it’s even for anymore. Art is asked to serve as a tool, to reflect values, to become part of a city’s DNA, to fulfil functions, shift perspectives, provide frameworks, point the way, or teach us about our past.

And yet, it is art that we humans have turned to since time immemorial in existential moments, when the world falls apart: in the space of farewells, in rituals of celebration, at the end of life, or during its most intense moments. For comfort, for energy, to recharge, to find hope, or to create shared stories. If art is truly to be part of life in an avalanche-like, decentralized present – might we need to let go, if only briefly, of what we think we know about it, and open ourselves to something else?

At Bonniers Konsthall, the exhibition Playa! asks that very question: What happens to art if we let go of familiar patterns of showing and speaking about it? Can artists and institutions break free? Can they open new ground, forge new paths? And if so, what might those paths be? As its central thesis, the exhibition wonders: What happens if we meet art on the terms of poetry? If we invite in its radical energy and, just for a moment, forget about its functions and intermediaries?

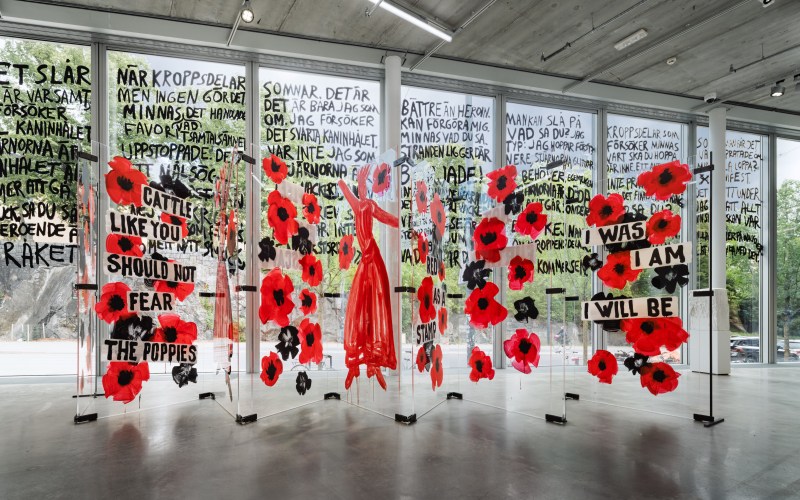

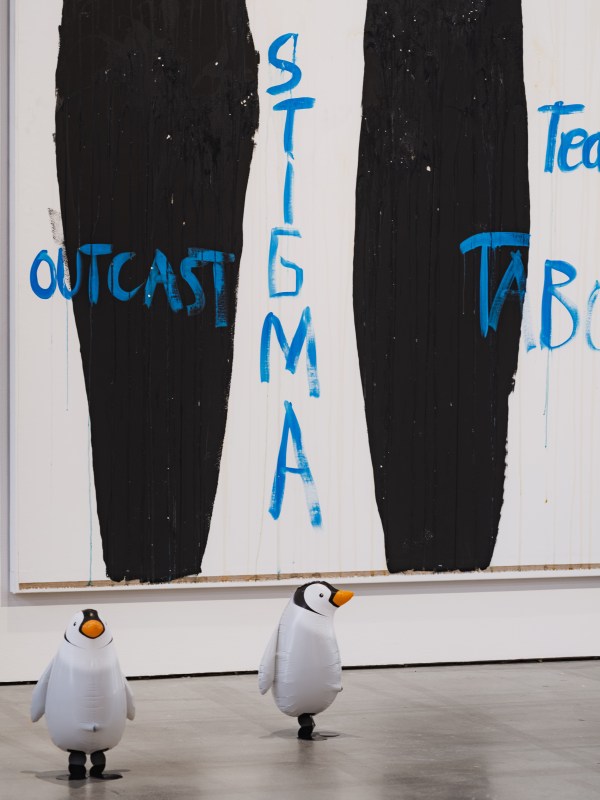

Playa! doesn’t centre around a specific question. But in a time of cascading shifts and unravelling certainties, it explores art and poetry as a necessary means of self-defence. Life on earth is such a good story, argues evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis in Margulis and mud, a performance by Essi Kausalainen featured in the exhibition. Surrounded by a hundred helium penguins, seven notice boards retired from public space, a secret bar, and rotten eggs thrown by an 82-year-old at her paintings in disgust at the cruelty of the world, one is hopefully prepared to agree.

For the exhibition, artist Alfred Boman has created the exhibition architecture. Poet Elis Monteverde Burrau has written the actual exhibition text directly onto the gallery windows. The collective coyote have been invited to run a bar. A large number of poets and writers have also been invited to read and engage in conversation as part of the program.

The exhibition as a whole has taken shape in dialogue between the artists, piece by piece, like a jigsaw puzzle coming together. In this way, the exhibition also functions as a kind of manifesto, a notice board, a proposal – one that probes the potential of aesthetic and poetic experience. Because surely art is still vast, wild, and free? Surely it can still jolt us from our slumber, help us rub the algorithms – or the despair – out of our eyes?

In the foreword to Kristin Ross’s The Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune (2008), which explores the poet’s relationship to his city in revolutionary times, Terry Eagleton writes: “Revolutions are as much about the breaking apart of identities as the forging of them, as much about the creation of fantasy and disorder as about political constitutions.”

So what does a new artistic revolution look like?

And what do we need to do to support it?

Text by Joanna Nordin, Artistic Director and the exhibition’s curator.